Protestant literature began with Trubar and ended shortly after his death, as his contemporaries were mostly his students. In addition to Trubar, the major Slovenian Protestant writers are Jurij Dalmatin, Adam Bohorič and Sebastjan Krelj.

Sebastjan Krelj (1538-1567) from the town of Vipava wrote 11 poems, and two books: Otročja biblija ('Children's Bible') in 1566, and the first part of Postila slovenska ('Slovenian Postil') in 1567. The former was created for educational purposes and also included the catechism in five languages, while the latter explains the gospels read on Sundays and holy days in lay terms. With regard to language and orthography, these writings meant a major step forward from Trubar, as Krelj had a better linguistic knowledge. His language is more pure, the orthography is consistent (with regard to sibilants), and he also introduced the use of diacritics in writing.

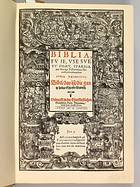

Jurij Dalmatin (about 1547–1589) decided to translate the Bible while studying abroad. He learned from his teacher Trubar. Between 1575 and 1580 he managed to print several religious books in Mandelc's print shop in Ljubljana. After long efforts he convinced the regional assemblies of Carniola, Styria and Carinthia to finance the printing of the whole Bible, which was published in Wittenberg in 1584. He also wrote a prayer book, catechism and a song book.

Dalmatin's Bible is the greatest and most important work of Slovenian Protestantism; it introduced Krelj's linguistic reforms and continued to be used by the Slovenian clergy for 200 years.

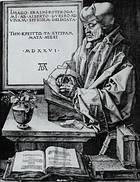

Adam Bohorič (about 1520–about 1599) came from the vicinity of Krško. He was the headmaster of the Latin school in Ljubljana, and later the region's school inspector. About 1580 he adapted a Latin-German-Slovene glossary; however, his most famous work is a grammar, Arcticae horulae ('Winter Hours'), which was published in 1584 in Wittenberg. Although it was scientifically questionable, as it is only an adaptation of a Latin grammar, its significance was enormous, as it is the first scientific document on Slovene. In the long introduction, Bohorič writes of the Slovenes as belonging to the great Slavic community, which boosted the patriotism of the intelligentsia. He also gave the name to the Bohorič alphabet (bohoričica), although Dalmatin deserves the greatest credit for its introduction.

A close connection with the Slovene environment did not prevent Trubar from being active in the European dimension, holding a self-confident pose among the most influential figures of the time, including Erasmus, King Maximilian II, Bishop Pietro Bonomo, and the theologians Matthias Flacius and Jacob Andreae.

Erasmus (1467-1563) taught ancient Greek at the University of Cambridge. While in England he wrote his most famous work The Praise of Folly.

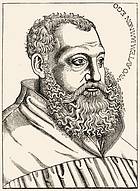

Pietro Bonomo – Bishop of Trieste, a humanist, supporter of the reforms in the Catholic church, mentor and patron of Primož Trubar. Within his circle he discussed the works of Erasmus, sometimes also in Slovene. They also read works by Luther, Zwingli and Calvin.

The Bishop of Koper Pietro Paolo Vergerio accepted Protestantism and fled to Germany in 1549. He helped Trubar promote the books.

Ivan Ungnad – a nobleman from Carinthia and Styria and former governor of Styria, who fled from the Habsburgs into the Protestant region of Germany and became the patron of Slovenian and other South Slavic writers of Protestant books. He founded the Biblican Institute in Urach and made Trubar the first headmaster.

Janez Mandelc – the printer and publisher who founded the first print shop in Ljubljana in 1575